|

Personal note:

The reason why Thor Heyerdahl is listed in this section on famous discoverers

and navigators is the fact that the documentary on Heyerdahl's Tigris

expedition, which I saw on television as a teenager was the beginning of an

ever growing personal interest in adventure, sailing and navigation.

I was extremely fascinated to learn that these adventurers on their pre-historical

raft were able to find their position on high seas using a simple optical instrument

called a sextant.

Much of Heyerdahl's anthropological work may be controversial, but his achievements

as expedition leader are indisputable outstanding and exceptional.

Exceptional also in the sense that we should be aware, that his way of conducting

international expeditions have become completely impossible these days.

Today paranoia and irrational anxiety are ruling the world, manifesting itself

in the unconditional controlling mania national administrations and secret

services are executing on their citizens making it impossible to even travel the

seas as a truly free man.

So in this sense, for me Thor Heyerdahl is one of the last of great adventurers

that were able to seek their fate without being shackled by an over-regulated

world administration.

His expeditions are also stories about a kind of freedom we have completely

lost over the last decades.

Thor Heyerdahl (1914-2002)

Thor Heyerdahl was a Norwegian explorer, adventurer, and scientist

best known for his famous voyages aboard the prehistoric rafts

Kon-Tiki, Ra and Tigris.

By crossing both the Atlantic and the Pacific in simple native rafts,

Heyerdahl showed that ancient peoples could have crossed much greater

distances than was previously imagined and that trade and cultural

exchange could have taken place between Africa and the Americas as

well as between Pacific Islanders and South Americans.

Thor Heyerdahl was born October 6, 1914 in the coastal village of Larvik,

Norway. Early on the young Heyerdahl developed a passion for camping and

other outdoors activities.

His love of natural science, led him to accumulate his own zoological collection.

And when he entered college, at the University of Oslo, he elected to specialize

in marine biology and geography.

Contact with a large collection of Polynesian artefacts, owned by a family

friend, focused his interest on the islands of the South Pacific.

In 1936, aided by financial backing from his father, Heyerdahl left school

and travelled with his wife, Liv, to the remote Polynesian island of Fatu Hiva.

Honeymooning in primitive bliss, the couple lived for a year among the indigenous

people and studied native lore and customs as well as indigenous fauna and flora.

Heyerdahl was intrigued by legends which claimed that the ancestors of Fatu Hiva

islanders had come from the east. But the only thing to the east was distant Peru.

Could islanders in tiny primitive craft have crossed such a vast distance?

But as Heyerdahl studied Pacific currents he became convinced that such a

crossing was highly possible. What's more, sweet potatoes, a food native to

South America, were also found on the island, as were some large statues

resembling artwork found in parts of South America.

Although it ran completely contrary to accepted anthropological theories, Heyerdahl

felt the islanders' claims of eastern ancestry deserved further investigation.

So he turned his field of research from zoology to anthropology and took a position

at the Museum of British Columbia.

There, as he studied the native tribes of the Pacific Northwest, he toyed

with the notion that natives travelling by small craft could have facilitated

contact between North and South America as well as the Pacific Islanders,

creating network of trade and cultural exchange.

Kon-Tiki expedition

Heyerdahl reasoned that it was foolish for academics to proclaim such

voyages impossible without first investigating the limits of the technology involved.

He resolved to do so himself and thus, studying traditional South American boat

building materials and crafts, he constructed a 45-foot balsa raft which he

named the Kon-Tiki.

On Kon-Tiki Heyerdahl and his crew sailed some 4300 miles across the Pacific,

landing on Raroia Atoll in the South Pacific on August 7, 1947.

Despite the primitive nature of their craft and despite their relative low

experience with it, Heyerdahl and his crew had demonstrated that early

contact between South Americans and Pacific Islanders was technically possible.

Heyerdahl's next mission was to search for clues pointing to actual contact between

the Americas and the Pacific isles. Over the next 50 years he studied language,

art, folklore, physical characteristics, and more in various parts of

South America and the Pacific.

But although some of his findings were quite compelling, anthropologists never

accepted his theory.

In part this was due to simple scepticism and bias. But over the years other

researchers began unearthing new archaeological, linguistic, and DNA evidence

that backed up the old notion of a western origin for Pacific Island peoples.

Some even accused Heyerdahl of having selected only that evidence which

supported his claims, while discarding any data that which did not fit

his preconceived conclusions.

But while Heyerdahl was willing to concede that a wave of west to east

colonization had taken place (i.e. not coming from the Americas but from

the direction of India and Southeastern Asia), he remained convinced that

his theory of transpacific contact was correct.

Native mariners, he argued surely made contact between the Islands and

the Americas.

Today some scientists grudgingly admit that trade between Pacific Islanders

and the Americas may have taken place from time to time.

But Heyerdahl's theory remains marginalized.

Heyerdahl meanwhile was not content to limit his theory of ocean hopping

to the Pacific. In fact he began to envision a broad network of cultural

and trade exchange that looped through the Pacific, Central America,

Africa, and even parts of ancient Europe. To prove his point he collected

images and lore of small craft that were markedly similar in various parts

of the world.

And to prove that such craft could have made the long journeys he suggested,

he also mounted additional ocean expeditions.

Heyerdahl was undaunted and studied ancient Egyptian tomb paintings to design

a papyrus boat that might prove a theory of cultural migration from Egypt

to South America.

The Ra expeditions

|

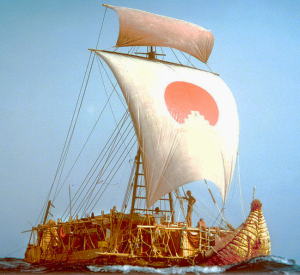

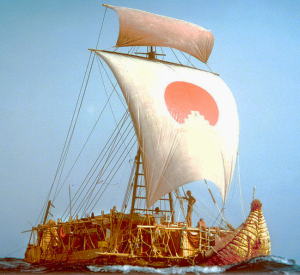

In 1969 and 1970, Heyerdahl built two boats from papyrus and attempted to cross

the Atlantic Ocean from Morocco in Africa.

Based on drawings and models from ancient Egypt, the first boat, named Ra

after the Egyptian Sun god, was constructed by boat builders from Lake Chad

using papyrus reed obtained from Lake Tana in Ethiopia and launched into the

Atlantic Ocean from Safi on the coast of Morocco.

After a number of weeks, Ra took on water after its crew made modifications

to the vessel that caused it to sag and break apart.

The ship was abandoned and the following year, another similar vessel,

Ra II, was built of totora by boat builders from Lake Titicaca in Bolivia and

likewise set sail across the Atlantic from Morocco, this time with great success.

The boat reached Barbados, thus demonstrating that mariners could have dealt

with trans-Atlantic voyages by sailing with the Canary Current. |

|

The Tigris expedition

|

The Ra expedition showed the possibility of early contact between Africa and the American continent.

Similarly, in 1977-78 aboard the Tigris, Heyerdahl demonstrated the feasibility

of trade and migration between the great civilizations of Mesopotamia, Egypt, and the

Indus Valley Civilization in what is now modern-day Pakistan.

Tigris - a 60 foot reed boat - was built in Iraq on the banks of the river Tigris.

Heyerdahl was sure the same type of vessels must have been used by the Sumerians 5000 years ago.

Tigris sailed with its international crew through the Persian Gulf then West to Pakistan

before turning East sailing through the indian ocean making its way into the Red Sea.

After about 5 months and 4000 miles at sea and still remaining completely seaworthy,

the Tigris was deliberately burnt in Djibouti, on April 3, 1978, as a protest against

the wars raging on every side in the Red Sea and Horn of Africa, which blocked the

expedition from sailing further into the Red Sea. |

|

Later live

Ultimately Heyerdahl's interest in the legends and pictographs of curved reed or wooden

boats led him to Azerbaijan, a Caucasus nation sandwiched between Russia to

the North and Turkey and Iran in the south.

There the 5,000 year old pictographs of crafts, reminiscent of ancient

Viking ships, seemed to support Heyerdahl's belief that significant

sea travel, and long distance river travel, had been going on much

earlier than most historians believed and in fairly "primitive" yet high

effective craft - craft that decayed leaving little trace of existence

or construction.

While many historians believed that significant boat travel occurred only

after the rise of large civilizations, Heyerdahl was certain that travel

by boat created trade and cultural exchange and thus spurred the growth

of the great civilizations. Thus, he claimed, boat travel was a leading

cause of civilization, not merely one of its products.

But the similarity between the pictographs and the ships of his Heyerdahl's

Norwegian ancestors had significance. They reminded him of ancient

legends which claimed that his people had originally come from the land of

Aser, east of the Black Sea. According to the scribes they were led north

from that land by their leader Odin, to escape the coming of the Romans.

Although many regarded Odin as merely a mythological figure, Roman expansion

was a historical fact.

And Roman presence in Azerbaijan could be reliably dated.

When Heyerdahl compared the timeline of the Roman presence in Azerbaijan

with the timeline of the reigns of the early Norwegian kings he found

apparent correlations, indicating the possibility of a Caucasian homeland

for the Norwegians and other Scandinavian peoples.

Additional archaeological and DNA evidence appears to lend credence

to the notion.

This discovery, coupled with his sea going expeditions aboard the Kon-Tiki

and so forth, only confirmed an important principle that Heyerdahl

already believed, if one digs deeply enough it can be shown that we are

all related, both culturally and biologically.

What's more, he argued, harping on national or racial differences and

using them to justify war and discrimination is foolish.

We are all one people under the skin. As an ardent environmentalist too,

Heyerdahl believed human beings would be better served by working together

to save the planet rather than trying to monopolize and exploit its

resources for the temporary gain of any one people.

Thor Heyerdahl continued his studies of cultural diffusion and of ancient

sea going societies well into his eighties, remaining an active lecturer

and world traveller.

But in April of 2002 he was diagnosed with a brain tumor.

He died a short time later in a hospital near his family retreat in

Colla Michari, Italy.

Although much of Heyerdahl's anthropological work continues to be

rejected by scientists, he opened the eyes of the public to the very

real fact that our assumptions about the past, and about what is possible,

can be wildly inaccurate.

And his expeditions on the sea proved that ancient peoples, although

using simple technologies, were capable of much greater feats of navigation

and travel than was previously realized.

The story of Heyerdahl's own voyages continues to fascinate both

adventurers and those who believe human history, is more complicated

than mainstream science admits.

Sources

1. "Tigris - op zoek naar de oorsprong", Thor Heyerdahl, 1979, bv Uitgeverij De Kern, Bussum Nederland

2. "Die Ra expeditie", Thor Heyerdahl, 1970, Teleboek nv, Bussum Nederland

3. "Early Man and the Ocean" - Review by Peter S. Bellwood, 1979, Institute of Archaeology, University of London

|