Francis Drake (ca. 1540 - 1596)

In 1567 Drake commanded the Judith in his kinsman John Hawkyns's ill-fated expedition

to the West Indies, and returned there several times to recover the losses sustained from

the Spaniards, his exploits gaining him great popularity in England.

In 1577 he set out with five ships for the Pacific, through the Straits of Magellan, but

after his fleet was battered by storm and fire, he alone continued in the Golden Hind.

He then struck out across the Pacific, reached the Pelew Is, and returned to England via

the Cape of Good Hope in 1580.

The following year, the queen visited his ship and knighted him. In 1585 he sailed with 25 ships

against the Spanish Indies, bringing home tobacco, potatoes, and the dispirited Virginian

colonists.

In the battle against the Spanish Armada, which raged for a week in the Channel (1588),

his seamanship and courage brought him further distinction.

In 1595 he sailed again to the West Indies, but died of dysentery off Porto Bello, Panama.

Early life

| ca. 1540 |

|

Born on the Crowndale estate of Lord Francis Russell, second earl of Bedford, Francis Drake was

the son of one of the latter's tenant farmers. His father was an ardent Protestant lay

preacher, an influence that was to have an immense effect on Drake's character.

His detestation of Catholicism had its origins not only in his father's teaching but

in his own early experiences, when his family had to flee the West Country during the

Catholic uprising of 1549. They made their way to Kent in southeastern England and,

in exchange for their former country cottage home, found lodging in one of the old naval

hulks that were moored near Chatham on the south bank of the Thames Estuary.

Had he stayed in Devon he might have become a yeoman farmer, but his family's poverty

drove him to sea while he was still a boy. When Drake was about 13 years old, he was

apprenticed to a small coastal vessel plying between North Sea ports. Thus, sailing

one of the harshest stretches of water in the world, he learned early how to handle

small vessels under arduous conditions. The knowledge of pilotage he acquired during

these years was to serve him in good stead throughout his life. The old sea captain

left Drake his ship when he died, so that Drake, thereafter, became his own master.

Drake might have spent all his life in the coastal trade but for the happy accident

that he was related to the powerful Hawkins family of Plymouth, Devon, who were then

embarking on trade with the New World - the New World that, as Drake never forgot,

had been "given" by Pope Alexander VI to the kingdom of Spain. When he was about 23,

dissatisfied with the limited horizons of the North Sea, he sold his boat and enlisted

in the fleet of the Hawkins family. Now he first saw the ocean swell of the Atlantic

and the lands where he was to make his fame and fortune. |

Voyages to the West Indies

| ca. 1565 |

|

On a voyage to the West Indies, as second in command, Drake had his first experience

of the Spaniards and of the way in which foreigners were treated in their realms;

their cargoes, for example, were liable to be impounded. At a later date he referred

to some "wrongs" that he and his companions had suffered - wrongs that he was determined

to right in the years to come.

His second voyage to the West Indies, this time in company

with John Hawkins, ended disastrously at San Juan de Ulza off the coast of Mexico, when

the English seamen were treacherously attacked by the Spanish and many of them

killed. Drake returned to England in command of a small vessel, the Judith, with

an even greater determination to have his revenge upon Spain and the Spanish king (Philip II).

Although the expedition was a financial failure, it served to make Drake's reputation,

for he had proved himself an outstanding seaman. People of importance, including Queen

Elizabeth I, who had herself invested in the venture, now heard his name.

In the years that followed he made two expeditions in small boats to the West Indies,

in order "to gain such intelligence as might further him to get some amend for his loss ..."

In 1572, having obtained from the Queen a privateering commission, which amounted to a

license to plunder in the King of Spain's lands, Drake set sail for America in command

of two small ships, the "Pasha," of 70 tons, and the "Swan" of 25 tons.

He was nothing if not ambitious, for his aim was to capture the important town of

Nombre de Dios, Panama. Although himself wounded in the attack, he and his men managed

to get away with a great deal of plunder, the foundation of his fortune.

Not content with this, he went on to cross the Isthmus of Panama. Standing on a high

ridge of land, he first saw the Pacific, that ocean hitherto barred to all but Spanish ships.

It was then, as he put it, that he "besought Almighty God of His goodness to give him life

and leave to sail once in an English ship in that sea."

His name as well as fortune was established by this expedition, and he returned to England

both rich and famous. Unfortunately, his return coincided with a moment when Queen Elizabeth

and King Philip II of Spain had reached a temporary truce. Although delighted with Drake's

success in the empire of her great enemy, Elizabeth could not officially acknowledge it.

Drake, who was as politically discerning as he was navigationally brilliant, saw that the

time was inauspicious and sailed with a small squadron to Ireland, where he served under

the Earl of Essex, who was then engaged in suppressing a rebellion in that strife-torn land.

This is an obscure period of Drake's life, and he does not emerge into the clear light

of history until two years later. |

Circumnavigation of the world

| 1577 |

|

In 1577 he was chosen as the leader of an expedition intended to pass around South

America through the Strait of Magellan and to explore the coast that lay beyond.

The object was to conclude trading treaties with the people who lived south of the Spanish

sphere of influence and, if possible, to explore an unknown continent that was rumoured to

lie far in the South Pacific.

The expedition was backed by the Queen herself. Nothing could have suited Drake better.

He had official approval to benefit himself and the Queen, as well as to cause the maximum

damage to the Spaniards. It was now that he met the Queen for the first time and heard from

her own lips that she "would gladly be revenged on the King of Spain for divers injuries

that I have received." He set sail in December with five small ships, manned by fewer

than 200 men, and reached the Brazilian coast in the spring of 1578. His flagship, the

" Pelican", which Drake later renamed " The Golden Hind" was only about 100 tons.

It seemed little enough with which to undertake a venture into the domain of the most powerful

monarch and empire in the world.

Upon arrival in South America, it was discovered that there was a plot against Drake,

and its leader, Thomas Doughty, was tried and executed. Drake was always a stern disciplinarian,

and he clearly did not intend to continue the venture without making sure that all his

small company were loyal to him.

Two of his smaller vessels, having served their purpose as store ships, were then abandoned,

after their provisions had been taken aboard the others, and, on Aug. 21, 1578, he entered

the Strait.

It took 16 days to sail through, after which Drake had his second view of the Pacific Ocean,

this time from the deck of an English ship.

Then, as he wrote, "God by a contrary wind and intolerable tempest seemed to set himself

against us".

During the gale, Drake's vessel and that of his second in command had been separated;

the latter, having missed a rendezvous with Drake, ultimately returned to England, presuming

that the " The Golden Hind" had sunk.

It was, therefore, only Drake's flagship that made its way into the Pacific and up the coast

of South America. He passed along the coast like a whirlwind, for the Spaniards were quite

unguarded, having never known a hostile ship in their waters.

He seized provisions at Valparamso, attacked passing Spanish merchantmen, and captured two

very rich prizes.

" The Golden Hind" was below her watermark, loaded with bars of gold and silver, minted

Spanish coinage, precious stones, and pearls, when he left South American waters to continue

his voyage around the world. Before sailing westward, however, he sailed to the north as far

as 48°N, on a parallel with Vancouver, to seek the Northwest Passage back into the Atlantic.

The bitterly cold weather defeated him, and he coasted southward to anchor just north of modern

San Francisco. He named the surrounding country "New Albion" and took possession of it in

the name of Queen Elizabeth.

In his search for a passage around the north of America he was the first European to sight

the west coast of what is now Canada.

In July 1579 he sailed west across the Pacific and after 68 days sighted a line of islands

(probably the remote Palau group). From there he went on to the Philippines, where he

watered ship before sailing to the Moluccas. There he was well received by the local sultan

and appears to have concluded a treaty with him giving the English the right to trade for spices.

Drake's deep-sea navigation and pilotage were always excellent, but in those totally uncharted

waters his ship struck a reef. He was able to get her off without any great damage and,

after calling at Java, set his course across the Indian Ocean for the Cape of Good Hope.

Two years after she had nosed her way into the Strait of Magellan, " The Golden Hind" came

back into the Atlantic with only 56 of the original crew of 100 men left aboard.

On Sept. 26, 1580, Francis Drake brought his ship into Plymouth Harbour.

She was laden with treasure and spices, and Drake's fortune was permanently made.

He thus became the first captain ever to sail his own ship around the world, the Portuguese

navigator Ferdinand Magellan having been killed before completing his circumnavigation;

and the first Englishman to sail the Pacific, the Indian Ocean, and the South Atlantic.

Despite Spanish protests about his piratical conduct while in their imperial waters,

Queen Elizabeth herself came aboard " The Golden Hind", which was lying at Deptford

in the Thames Estuary, and personally bestowed knighthood on the farmer's son. |

Mayor of Plymouth

| 1581 |

|

In the same year, 1581, Drake was made mayor of Plymouth, an office he fulfilled with

the same thoroughness that he had shown in all other matters. He organized a water

supply for Plymouth that served the city for 300 years. In 1585 he married again,

his first wife, a Cornish woman named Mary Newman, whom he had married in 1569,

having died in 1583.

His second wife, Elizabeth Sydenham, was an heiress and the daughter of a local

Devonshire magnate, Sir George Sydenham. In keeping with his new station, Drake bought

himself a fine country house-Buckland Abbey (now a national museum) a few miles from Plymouth.

Drake's only grief was that neither of his wives bore him any children.

During these years of fame when Drake was a popular hero, he could always obtain volunteers

for any of his expeditions.

But he was very differently regarded by many of his great contemporaries.

Such well-born men as the naval commander Sir Richard Grenville and the navigator and

explorer Sir Martin Frobisher disliked him intensely. He was the parvenu, the rich

but common upstart, with West Country manners and accent and with none of the courtier's graces.

Drake had even bought Buckland Abbey from the Grenvilles by a ruse, using an intermediary,

for he knew that the Grenvilles would never have sold it to him directly.

It is doubtful, in any case, whether he cared about their opinions, so long as he

retained the goodwill of the Queen.

This was soon enough demonstrated, for in 1585 Elizabeth placed him in command of a

fleet of 25 ships.

Hostilities with Spain had broken out once more, and he was ordered to cause as much

damage as possible to the Spaniards' overseas empire. Drake fulfilled his commission,

capturing Santiago in the Cape Verde Islands and taking and plundering the cities of

Cartagena in Colombia, St. Augustine in Florida, and San Domingo, Hispaniola.

The effect of his triumph in the West Indies was cataclysmic.

Spanish credit, both moral and material, almost foundered under the losses.

The Bank of Spain broke, the Bank of Venice (to which Philip II was principal debtor)

nearly foundered, and the great German bank of Augsburg refused to extend the Spanish

monarch any further credit. Even Lord Burghley, Elizabeth's principal minister, who

had never approved of Drake or his methods, was forced to concede that "Sir Francis

Drake is a fearful man to the King of Spain." |

Defeat of the Spanish Armada

| 1586 |

|

By 1586 it was known that Philip II was preparing a fleet for what was called

"The Enterprise of England," and that he had the blessing of Pope Sixtus V to

conquer the heretic island and return it to the fold of Rome.

Sir Francis Drake was given carte blanche by the Queen to "impeach the provisions

of Spain." In the following year, with a fleet of some 30 ships, he showed that her

trust in him had not been misplaced.

He stormed into the Spanish harbour of Cadiz and in 36 hours destroyed thousands of

tons of shipping and supplies, all of which had been destined for the Armada.

This action, which he laughingly referred to "as singeing the king of Spain's beard,"

was sufficient to delay the invasion fleet for a further year.

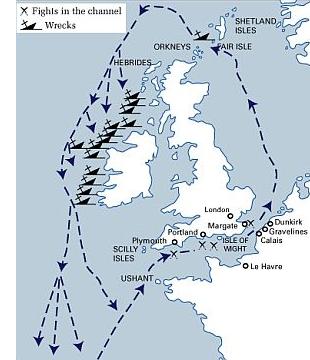

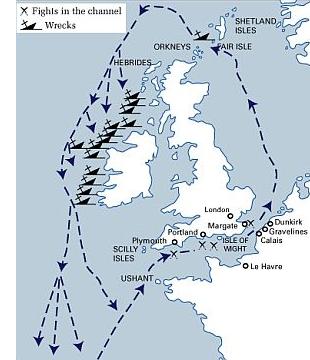

But the resources of Spain were such that by July 1588 the Armada was in the English

Channel. Lord Howard had been chosen as English admiral to oppose, with Drake as

his vice admiral. On 16 July peace negotiations were abandoned, and the English fleet stood

prepared, if ill-supplied, at Plymouth, awaiting news of Spanish movements.

The Armada was delayed by bad weather.

On 20 July the English fleet was off Eddystone Rocks, with the Armada upwind to the west.

That night, in order to execute their attack, the English tacked upwind of the Armada,

thus gaining the weather gage, a significant advantage.

At daybreak on 21 July the English fleet engaged the Armada off Plymouth near the Eddystone rocks.

The Armada was in a defensive formation in a crescent convexed towards the East.

The galleons and great ships were concentrated in the centre and at the tips of the crescent's

horns giving cover to the transports and supply ships in between.

Opposing them the English were in two sections, Drake to the north in Revenge with 11 ships,

and Howard to the south in Ark Royal with the bulk of the fleet.

Given the Spanish advantage in close quarter fighting, the English ships used their superior

speed and manoeuvrability to keep beyond grappling range and bombarded the Spanish ships

from a distance with cannon fire. However the distance was too great for this to be

effective, and at the end of the first day's fighting neither fleet had lost a ship,

though two of the Spanish ships, the carrack Rosario and the galleon San Salvador,

were abandoned after they collided. When night fell, Francis Drake turned his ship

back to loot the ships, capturing supplies of much-needed gunpowder, and gold.

However, Drake had been guiding the English fleet by means of a lantern.

Because he snuffed out the lantern and slipped away for the abandoned Spanish ships,

the rest of his fleet became scattered and was in complete disarray by dawn.

It took an entire day for the English fleet to regroup and the Armada gained a day's grace.

The English ships then used their superior speed and manoeuvrability to catch up with

the Spanish fleet after a day of sailing.

On 23 July the English fleet and the Armada engaged once more, off Portland. This time a

change of wind gave the Spanish the weather-gage, and they sought to close with the English,

but were foiled by the smaller ships' greater manoeuvrability. At one point Howard formed

his ships into a line of battle, to attack at close range bringing all his guns to bear,

but this was not followed through and little was achieved.

At the Isle of Wight the Armada had the opportunity to create a temporary base in protected

waters of the Solent and wait for word from Parma's army. In a full-scale attack, the English

fleet broke into four groups - Martin Frobisher of the Aid now also being given command

over a squadron - with Drake coming in with a large force from the south.

At the critical moment Medina Sidonia sent reinforcements south and ordered the Armada

back to open sea to avoid the Owers sandbanks. There were no secure harbours nearby,

so the Armada was compelled to make for Calais, without regard to the readiness of Parma's army.

On 27 July, the Armada anchored off Calais in a tightly packed defensive crescent formation,

not far from Dunkirk, where Parma's army, reduced by disease to 16,000, was expected to be waiting,

ready to join the fleet in barges sent from ports along the Flemish coast.

Communications had proven to be far more difficult than anticipated, and it only now became

clear that this army had yet to be equipped with sufficient transport or assembled in port,

a process which would take at least six days, while Medina Sidonia waited at anchor; and that

Dunkirk was blockaded by a Dutch fleet of thirty flyboats under Lieutenant-Admiral Justin

of Nassau. Parma desired that the Armada send its light petaches to drive away the Dutch,

but Medina Sidonia could not do this because he feared that he might need these ships for

his own protection. There was no deepwater port where the fleet might shelter - always

acknowledged as a major difficulty for the expedition - and the Spanish found themselves

vulnerable as night drew on.

At midnight on 28 July, the English set alight eight fireships, sacrificing regular warships

by filling them with pitch, brimstone, some gunpowder and tar, and cast them downwind among

the closely anchored vessels of the Armada. The Spanish feared that these uncommonly large

fireships were "hellburners", specialised fireships filled with large gunpowder charges,

which had been used to deadly effect at the Siege of Antwerp. Two were intercepted and

towed away, but the remainder bore down on the fleet. Medina Sidonia's flagship and the

principal warships held their positions, but the rest of the fleet cut their anchor cables

and scattered in confusion. No Spanish ships were burnt, but the crescent formation had been

broken, and the fleet now found itself too far to leeward of Calais in the rising southwesterly

wind to recover its position. The English closed in for battle.

With its superior manoeuvrability, the English fleet provoked Spanish fire while

staying out of range. The English then closed, firing repeated and damaging broadsides

into the enemy ships. This also enabled them to maintain a position to windward so

that the heeling Armada hulls were exposed to damage below the water line.

Many of the gunners were killed or wounded, and the task of manning the cannons often

fell to the regular foot soldiers on board, who did not know how to operate the complex guns.

The prevailing southerly winds left to Medina Sidonia no other option as to chart a course

home to Spain, by a very hazardous route.

In September 1588 the Armada sailed around Scotland and Ireland into the North Atlantic.

The Spanish ships were beginning to show wear from the long voyage, and some were kept together

by having their hulls bundled up with cables. Supplies of food and water ran short.

The intention would have been to keep well to the west of the coast of Scotland and Ireland,

in the relative safety of the open sea. However, there being at that time no way of accurately

measuring longitude, the Spanish were not aware that the Gulf Stream was carrying them north

and east as they tried to move west, and they eventually turned south much further to the

east than planned, a devastating navigational error.

Off the coasts of Scotland and Ireland the fleet ran into a series of powerful westerly gales,

which drove many of the damaged ships further towards the lee shore.

Because so many anchors had been abandoned during the escape from the English fireships off

Calais, many of the ships were incapable of securing shelter as they reached the coast

of Ireland and were driven onto the rocks.

The home-bound Spanish fleet was dispersed and largely wrecked.

Drake was England's hero, achieving a popularity never to be equalled by any man until

Horatio Nelson emerged more than 200 years later. |

Last years

| 1596 |

|

Drake's later years were not happy, however. An expedition that he led to Portugal

proved abortive, and his last voyage, in 1596, against the Spanish possessions in

the West Indies was a failure, largely because the fleet was decimated by fever.

Drake himself succumbed and was buried at sea off the town of Puerto Bello, Panama. |

|

Upon arrival in South America, it was discovered that there was a plot against Drake,

and its leader, Thomas Doughty, was tried and executed. Drake was always a stern disciplinarian,

and he clearly did not intend to continue the venture without making sure that all his

small company were loyal to him.

Two of his smaller vessels, having served their purpose as store ships, were then abandoned,

after their provisions had been taken aboard the others, and, on Aug. 21, 1578, he entered

the Strait.

It took 16 days to sail through, after which Drake had his second view of the Pacific Ocean,

this time from the deck of an English ship.

Then, as he wrote, "God by a contrary wind and intolerable tempest seemed to set himself

against us".

During the gale, Drake's vessel and that of his second in command had been separated;

the latter, having missed a rendezvous with Drake, ultimately returned to England, presuming

that the "The Golden Hind" had sunk.

It was, therefore, only Drake's flagship that made its way into the Pacific and up the coast

of South America. He passed along the coast like a whirlwind, for the Spaniards were quite

unguarded, having never known a hostile ship in their waters.

He seized provisions at Valparamso, attacked passing Spanish merchantmen, and captured two

very rich prizes.

"The Golden Hind" was below her watermark, loaded with bars of gold and silver, minted

Spanish coinage, precious stones, and pearls, when he left South American waters to continue

his voyage around the world. Before sailing westward, however, he sailed to the north as far

as 48°N, on a parallel with Vancouver, to seek the Northwest Passage back into the Atlantic.

The bitterly cold weather defeated him, and he coasted southward to anchor just north of modern

San Francisco. He named the surrounding country "New Albion" and took possession of it in

the name of Queen Elizabeth.

In his search for a passage around the north of America he was the first European to sight

the west coast of what is now Canada.

Upon arrival in South America, it was discovered that there was a plot against Drake,

and its leader, Thomas Doughty, was tried and executed. Drake was always a stern disciplinarian,

and he clearly did not intend to continue the venture without making sure that all his

small company were loyal to him.

Two of his smaller vessels, having served their purpose as store ships, were then abandoned,

after their provisions had been taken aboard the others, and, on Aug. 21, 1578, he entered

the Strait.

It took 16 days to sail through, after which Drake had his second view of the Pacific Ocean,

this time from the deck of an English ship.

Then, as he wrote, "God by a contrary wind and intolerable tempest seemed to set himself

against us".

During the gale, Drake's vessel and that of his second in command had been separated;

the latter, having missed a rendezvous with Drake, ultimately returned to England, presuming

that the "The Golden Hind" had sunk.

It was, therefore, only Drake's flagship that made its way into the Pacific and up the coast

of South America. He passed along the coast like a whirlwind, for the Spaniards were quite

unguarded, having never known a hostile ship in their waters.

He seized provisions at Valparamso, attacked passing Spanish merchantmen, and captured two

very rich prizes.

"The Golden Hind" was below her watermark, loaded with bars of gold and silver, minted

Spanish coinage, precious stones, and pearls, when he left South American waters to continue

his voyage around the world. Before sailing westward, however, he sailed to the north as far

as 48°N, on a parallel with Vancouver, to seek the Northwest Passage back into the Atlantic.

The bitterly cold weather defeated him, and he coasted southward to anchor just north of modern

San Francisco. He named the surrounding country "New Albion" and took possession of it in

the name of Queen Elizabeth.

In his search for a passage around the north of America he was the first European to sight

the west coast of what is now Canada.  During these years of fame when Drake was a popular hero, he could always obtain volunteers

for any of his expeditions.

But he was very differently regarded by many of his great contemporaries.

Such well-born men as the naval commander Sir Richard Grenville and the navigator and

explorer Sir Martin Frobisher disliked him intensely. He was the parvenu, the rich

but common upstart, with West Country manners and accent and with none of the courtier's graces.

Drake had even bought Buckland Abbey from the Grenvilles by a ruse, using an intermediary,

for he knew that the Grenvilles would never have sold it to him directly.

It is doubtful, in any case, whether he cared about their opinions, so long as he

retained the goodwill of the Queen.

During these years of fame when Drake was a popular hero, he could always obtain volunteers

for any of his expeditions.

But he was very differently regarded by many of his great contemporaries.

Such well-born men as the naval commander Sir Richard Grenville and the navigator and

explorer Sir Martin Frobisher disliked him intensely. He was the parvenu, the rich

but common upstart, with West Country manners and accent and with none of the courtier's graces.

Drake had even bought Buckland Abbey from the Grenvilles by a ruse, using an intermediary,

for he knew that the Grenvilles would never have sold it to him directly.

It is doubtful, in any case, whether he cared about their opinions, so long as he

retained the goodwill of the Queen. On 27 July, the Armada anchored off Calais in a tightly packed defensive crescent formation,

not far from Dunkirk, where Parma's army, reduced by disease to 16,000, was expected to be waiting,

ready to join the fleet in barges sent from ports along the Flemish coast.

Communications had proven to be far more difficult than anticipated, and it only now became

clear that this army had yet to be equipped with sufficient transport or assembled in port,

a process which would take at least six days, while Medina Sidonia waited at anchor; and that

Dunkirk was blockaded by a Dutch fleet of thirty flyboats under Lieutenant-Admiral Justin

of Nassau. Parma desired that the Armada send its light petaches to drive away the Dutch,

but Medina Sidonia could not do this because he feared that he might need these ships for

his own protection. There was no deepwater port where the fleet might shelter - always

acknowledged as a major difficulty for the expedition - and the Spanish found themselves

vulnerable as night drew on.

On 27 July, the Armada anchored off Calais in a tightly packed defensive crescent formation,

not far from Dunkirk, where Parma's army, reduced by disease to 16,000, was expected to be waiting,

ready to join the fleet in barges sent from ports along the Flemish coast.

Communications had proven to be far more difficult than anticipated, and it only now became

clear that this army had yet to be equipped with sufficient transport or assembled in port,

a process which would take at least six days, while Medina Sidonia waited at anchor; and that

Dunkirk was blockaded by a Dutch fleet of thirty flyboats under Lieutenant-Admiral Justin

of Nassau. Parma desired that the Armada send its light petaches to drive away the Dutch,

but Medina Sidonia could not do this because he feared that he might need these ships for

his own protection. There was no deepwater port where the fleet might shelter - always

acknowledged as a major difficulty for the expedition - and the Spanish found themselves

vulnerable as night drew on.