Christopher Columbus (1451 - 1506)

The Norwegian Viking navigators were the first European sailors who not only by

accident were blown onto the Canadian coast on their regular trips to Greenland,

but who also tried to settle in north America 500 years before Columbus re-discovered

this continent.

When the ages of discoveries started in the 15th century, Columbus is widely thought

to have been the first to sail across the Atlantic Ocean and make landfall on the

American continent.

His voyages across the Atlantic were made under the sponsorship of the Monarchs of

Aragon, Castile, and Leon in Spain and were motivated by the quest of a westward

access to the wealthy Indian markets, promising fame and fortune for its discoverers

and sponsors.

| 1451 |

|

Christopher Columbus was born in Genoa, Italy between Aug. 26 and Oct. 31 1451.

He was the eldest son of Domenico Colombo, a Genoese wool worker and merchant,

and Susanna Fontanarossa, his wife.

In 1473 Columbus began his apprenticeship as business agent for some important trading

families of Genoa.

Later he allegedly made a trip to Chios, a Genoese colony in the Aegean Sea.

In May 1476, he took part in an armed convoy sent by Genoa to carry a valuable cargo

to northern Europe.

He docked in Bristol, England; Galway, Ireland and was possibly in Iceland in 1477.

In 1479 Columbus reached his brother Bartolomeo in Lisbon, who was working as

a cartographer there.

He continued trading for his Genoese employers.

Between 1482 and 1485 Columbus traded along the coasts of West Africa,

reaching the Portuguese trading post of Elmina at the Guinea coast.

Ambitious, Columbus eventually learned Latin, as well as Portuguese and Castilian,

and read widely about astronomy, geography, and history.

Under the Mongol Empire's hegemony over Asia, Europeans had long enjoyed a safe

land passage, the so-called "Silk Road", to China and India, which were sources

of valuable goods such as silk, spices, and opiates.

With the fall of Constantinople to the Ottoman Turks in 1453, the land route to

Asia became much more difficult and dangerous.

Portuguese navigators, under the leadership of King John II, sought to reach Asia

by sailing around Africa. Major progress in this quest was achieved in 1488,

when Bartolomeu Dias reached the Cape of Good Hope, in what is now South Africa.

Meanwhile, in the 1480s the Columbus brothers had developed a different plan to

reach the Indies (then construed roughly as all of south and east Asia) by sailing

west across the "Ocean Sea", i.e., the Atlantic.

From 1482 to 1485 Columbus tried to convince King John II of Portugal to support

his plan of sailing westward to India.

But the King's advisers had the (correct) opinion that Columbus's estimation of the

distance to the West Indies was far too low and rejected the plan.

After Bartolomeu Dias had completed the exploration of the eastern sea route to Asia

in 1488, King John was no longer interested in Columbus's project, so the Columbus

brothers sought for support at other European courts in Genoa, Venice and London,

but without any success.

Ultimately, after tedious lobbying at the Spanish court and two years of negotiations,

he was finally able to get some financial support and in 1492, with some additional

sponsorship of Genoese merchants, Christopher Columbus was able to set up a small

expedition and to pursue his plan of reaching the Indies by sailing westward over

the Atlantic.

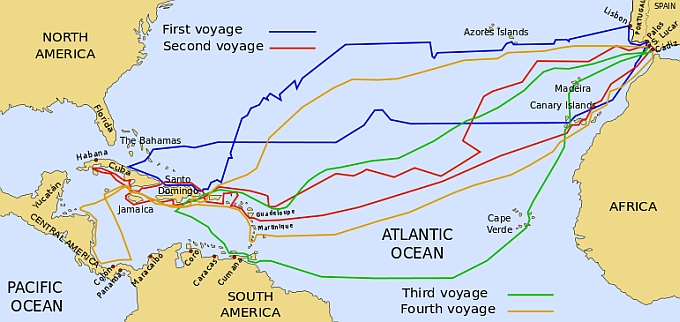

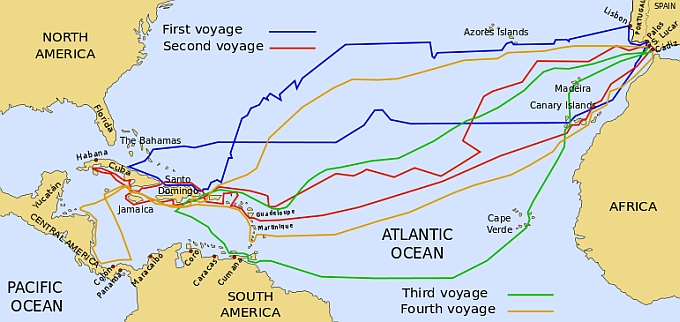

Between 1492 and 1503, Columbus completed four round-trip voyages between Spain and

the Americas, all of them under the sponsorship of the Crown of Castile.

Since these voyages marked the beginning of the European exploration and colonization of

the American continents, they are regarded of enormous significance in Western history.

|

First Transatlantic Voyage (Aug. 1492 - Mar. 1493)

| 1492 |

|

Christopher Columbus departed on his first voyage from the port of Palos

(near Huelva) in southern Spain, on August 2, 1492, in command of three ships:

the Santa Maria, the Niña and the Pinta.

He had a total of 87 crewmen.

His ships were rather fat and slow, designed for hauling cargo, not for exploration.

Over several days, Columbus's ships would average a little less than 4 knots.

Columbus first called at Gomera (Canary Islands), the westernmost Spanish possessions.

He was delayed there for four weeks by calm winds and the need for repair and refit

of his ships.

Columbus left the island of Gomera on September 6, 1492, but calms again left him

within sight of the western island of Hierro until September 8.

36 days after his departure from Gomera, on October 12, 1492, Christopher Columbus's

expedition made landfall somewhere in the Bahamas.

Columbus visited five islands in the Bahamas before reaching Cuba. He named these

(in order) San Salvador, Santa Maria de la Concepcion, Fernandina, Isabela, and

Las Islas de Arena. The last of these has been identified (almost universally)

with the modern Ragged Islands in the Bahamas.

The first four are in dispute and are still object to academic discussions.

So after five hundred years it is still unknown where Columbus first set foot

upon the shores of the new world.

Sailing further from the Bahama islands, Columbus arrived at Cuba on October 29. 1492.

While sailing north of Cuba on November 22, Martín Alonso Pinzón, captain

of the Pinta, deserts the expedition off Cuba and sailed on his own in search

of an island called "Babeque," where he had been told by his native guides

that there was much gold.

Columbus continued with the Santa Maria and Niña eastward,

and arrived at Hispaniola on December 5. On December 25. 1492 the flagship

Santa Maria grounded on a reef off Hispaniola and sank the next day.

Columbus used the remains of the ship to build a fort on shore, which he named

La Navidad (Christmas). The tiny Niña could not hold all of the

remaining crew, so Columbus was forced to leave about 40 men at La Navidad

to await his return from Spain. Columbus departed from La Navidad on

January 2, 1493.

Now down to just one ship, Columbus continued eastward along the coast of

Hispaniola, and was surprised when he came upon the Pinta on January 6.

Columbus's anger at Pinzón was eased by his relief at having another ship

for his return to Spain.

The two ships departed Hispaniola from Samana Bay (in the modern Dominican Republic)

on January 16, but were again separated by a fierce storm in the North Atlantic

on February 14; Columbus and Pinzón each believed that the other had perished.

Columbus sighted the island of Santa Maria in the Azores the next day.

He arrived at Lisbon on March 4, and finally made it back to his home

port of Palos on March 15, 1493.

Meanwhile, Pinzón and the Pinta had missed the Azores and arrived at

the port of Bayona in northern Spain. After a stop to repair the damaged

ship, the Pinta limped into Palos just hours after the Niña.

Pinzón had expected to be proclaimed a hero, but the honor had already been

given to Columbus. Pinzón died a few days later.

|

Second Transatlantic Voyage (Sep. 1494 - Jun. 1496)

| 1494 |

|

After the success of Columbus's first voyage, he had little trouble convincing

the Spanish Sovereigns, Ferdinand and Isabela, to follow up immediately with a

second voyage.

Unlike the exploratory first voyage, the second voyage was a massive colonization

effort, comprising seventeen ships and over a thousand men.

This second voyage brought European livestock (horses, sheep, and cattle) to

America for the first time.

Although Columbus kept a log of his second voyage, only very small fragments

survived. Most of what we know comes from indirect references or from accounts

of others on the voyage.

The fleet left Hierro in the Canary Islands on October 13, 1493.

Hoping to make a landfall at Hispaniola (where Columbus had left 40 men the

previous January), the fleet kept a constant course of west-southwest from

Hierro and sighted Dominica in the West Indies at dawn on Sunday, November 3.

The transatlantic passage of only 21 days was remarkably fast.

During the next two weeks, the fleet moved north from Dominica, discovering

the Leeward Islands, Virgin Islands, and Puerto Rico before arriving at

Hispaniola on November 22.

Returning to his fortress at Navidad on November 28, Columbus found that

the fort had been burned and that the men he had left there on the first

voyage were dead. Some of the men had abandoned the fort in the intervening

months, and some of the rest had raided an inland tribe and kidnapped their

women. The men of that tribe retaliated by destroying Navidad and killing

the few remaining Spaniards.

Columbus then sailed eastward along the coast of Hispaniola, looking for a

place to found a new colony. On December 8, he anchored at a good spot and

founded a new town he named La Isabela, after the Spanish queen.

The next several months were spent in establishing the colony and exploring

the interior of Hispaniola.

On April 24, 1494, Columbus set sail from Isabela with three ships, in an

effort to find the mainland of China, which he was still convinced must be nearby.

He reached Cuba on April 30 and cruised along its southern coast.

But soon he learned of an island to the south that was rumoured to be rich with gold.

Columbus left Cuba on May 3rd, and anchored at Jamaica two days later.

But the reception he received from the Indians was mostly hostile, and since

he had still not found the mainland, he left Jamaica on May 13, returning to

Cuba the following day.

The Admiral soon found that the southern coast of Cuba is dotted with shoals

and small islands, making exploration treacherous.

Making slow progress in difficult conditions, Columbus press westward for

several weeks until finally giving up the quest on June 13, 1494.

But not wanting to admit that his search for the mainland was a failure,

Columbus ordered each man in his crews to sign a document and swear that

Cuba was so large that it really must be the mainland.

The voyage back to Hispaniola was even worse, since they now had to rethread

the shoals and islands they had come through before, and now they had a headwind

to work against. After four weeks, tired of the incessant headwinds, Columbus

again turned south for Jamaica and confirmed that it was indeed an island.

Columbus finally returned to Hispaniola on August 20, 1494, and proceeded

eastward along the unknown southern coast. But by the end of September,

Columbus was seriously ill. His crew abandoned further explorations and

returned to the colony at La Isabela.

Over the next eighteen months Columbus worked, mostly without success, at his job

of colonial governor. His relations with the Spanish colonists were poor.

Relations with many of the indigent tribes had soured too, and war soon broke out

between the Spaniards and some of the tribes.

But the Spanish had a huge technological advantage, and the warfare was grossly

one-sided killing many indigenous.

Even more were captured and forced to work at the ungrateful job of finding gold.

In the spring of 1496, they were running out of supplies brought from Spain and

Columbus decided to return and apply for more support of the crown in establishing

a west-indian colony.

Columbus set sail from Isabela on March 10, 1496, bound home for Spain with

two ships. They made landfall at the coast of Portugal on June 8, completing

the second trans-atlantic voyage.

|

Third Transatlantic Voyage (May. 1498 - Oct. 1500)

| 1498 |

|

On the third voyage (May 30, 1498 - October, 1500) Columbus and his expedition

reached Trinidad and Venezuela and the Orinoco River delta.

Columbus left the port of Sanlucar in southern Spain on May 30, 1498 with

six ships, bound for the New World on his third voyage. After stopping at the

islands of Porto Santo and Madeira, the fleet arrived at Gomera in the

Canary Islands on June 19.

At this point, the fleet split into two squadrons: three ships sailed

directly for Hispaniola with supplies for the colonists there; but the other

three, commanded by Columbus himself, were on a mission of exploration,

attempting to find any lands south of the known islands in the Indies.

The Admiral sailed first to the Cape Verde Islands, where he was unsuccessful

in his attempts to obtain cattle.

He sailed southwest from the Cape Verdes on July 4, but by the 13th they had

made only 120 leagues.

At this point, the fleet was becalmed in the Doldrums, an area off the coast

of equatorial Africa notorious for its lack of winds.

After drifting eight days in calm and heat, winds returned on the 22nd,

and Columbus set their course West.

By the morning of July 31 water was running short, so the Admiral decided

to steer directly for Dominica, the island he had discovered on his second voyage.

After changing course to north by east, the fleet sighted an island in the

west at noon that same day.

Because the island had three hills, Columbus, who was very devoutly religious,

named it Trinidad, after the Holy Trinity.

The fleet obtained water on the south coast of Trinidad, and in the process

sighted the coast of South America, the first Europeans to see that continent.

Between South America and Trinidad lies the Gulf of Paria, which Columbus explored

between August 4th and August 12th.

On the morning of the 13th, the fleet sailed out of the Gulf of Paria at its northern

entrance and coasted west along the mainland for the next three days,

reaching the island of Margarita.

Columbus's health was poor at this time, and he now ordered the fleet to sail

for Hispaniola on a northwest by north course.

They arrived off southern Hispaniola on August 19, 1498.

Arriving at the new city of Santo Domingo, Columbus discovered that disgruntled

colonists had staged a revolt against his rule.

He was unable to put down the revolt, and eventually agreed to peace on

humiliating terms.

But the malcontents continued to grumble, and the amount of gold received

from the New World continued to be disappointingly small, both for the colonists

and the Sovereigns.

Accordingly, Ferdinand and Isabela appointed Francisco de Bobadilla as

royal commissioner, with powers above those of Columbus himself.

When Bobadilla arrived in Santo Domingo, he immediately had Columbus arrested,

and in October of 1500 the Admiral was sent home to Spain in shackles.

He was removed from the governorship of Hispaniola in 1499, his chief patron,

Queen Isabella, died in 1504, and his efforts to recover his governorship

of the "Indies" from King Ferdinand were, in the end, unavailing.

|

Last Transatlantic Voyage (May. 1502 - Nov. 1504)

| 1502 |

|

On the fourth voyage in the West Indies, Columbus sailed from Cape Honduras

to the Mosquito Coast of Nicaragua, Costa Rica, Veragua, and Panama.

On May 11, 1502, four old ships and 140 men under Columbus's command put

to sea from the port of Cadiz.

Among those in the fleet were Columbus's brother Bartholomew, and Columbus's

younger son Fernando, then just thirteen years old.

The nominal purpose of the trip was to find a strait linking the Indies

(which Columbus still thought to be part of Asia) with the Indian Ocean.

This strait was known to exist, since Marco Polo had traversed it on his way

back from China.

In effect, Columbus was looking for the Strait of Malacca (which is really

near Singapore) in Central America.

At age fifty-one, Columbus was old, sick, and no longer welcome in his old

home base of Hispaniola.

He arrived at Santo Domingo on June 29, 1502, and requested that he be

allowed to enter the harbour to shelter from a storm that he saw coming.

He also advised the treasure fleet assembling in the harbour to stay put

until the storm had passed.

His request was treated with contempt by Nicolas de Ovando, the local

governor, who denied Columbus the port and sent the treasure fleet on its way.

Columbus was forced to shelter his ships in a nearby estuary and when the

hurricane hit, the treasure fleet was caught at sea, and twenty ships were sunk.

Nine others limped back into Santo Domingo, and only one made it safely

to Spain.

Columbus's four ships all survived the storm with moderate damage.

Columbus arrived at the coast of Honduras at the end of July, and spent

the next two months working down the coast, beset by more storms and headwinds.

When they arrived at present-day Panama, they found two important things.

First, they learned from the natives that there was another ocean just a

few days march to the south.

This convinced Columbus that he was near enough the strait that he had

proved his point.

But more importantly, the natives had many gold objects that the Spaniards

traded for.

This made the region, which Columbus named Veragua, very valuable.

After coasting east along Panama until the area rich in gold petered out,

Columbus tried to return to Veragua but was again beset by storms and contrary winds.

Finally, Columbus returned to the mouth of the Rio Belen (western Panama) on

January 9, 1503, and made it his headquarters for exploration, building

a garrison fort there.

As he was preparing to return to Spain, he took three of his ships out

of the river, leaving one with the garrison.

The next day, April 6, the river lowered so much that the remaining ship was

trapped in the river by a sandbar across the river mouth.

At this moment, a large force of Indians attacked the garrison.

The Spanish managed to hold off the attack, but lost a number of men and

realized that the garrison could not be held for long.

Columbus abandoned the ship in the river, and rescued the remaining members

of the garrison.

The three ships, now badly leaking from shipworm, sailed for home on April 16.

One of the remaining ships had to be abandoned almost immediately because it

was no longer seaworthy, and the remaining two crawled slowly upwind in a game

effort to make it to Hispaniola.

They didn't make it. Off the coast of Cuba, they were hit by yet another storm,

the last of the ship's boats was lost, and one of the caravels was so badly damaged

that she had to be taken in tow by the flagship.

Both ships were leaking very badly now, and water continued to rise in the

hold in spite of constant pumping by the crew.

Finally, able to keep them afloat no longer, Columbus beached the sinking

ships in St. Anne's Bay, Jamaica, on June 25, 1503. Since there was no Spanish

colony on Jamaica, they were marooned.

For a year Columbus and his men would remain stranded on Jamaica.

Diego Mendez, one of Columbus's captains, was able to buy a canoe from a local chief

and together with some natives sailed it to Hispaniola.

He was promptly detained by governor Ovando outside the city for the next

seven months, and was refused to use a caravel to rescue the expedition.

Meanwhile, half of those left on Jamaica staged a mutiny against Columbus,

which he eventually put down.

Columbus, in a desperate effort to induce the natives to provision him and his

hungry men, successfully won the favor of the natives by correctly predicting

a lunar eclipse for 29 February 1504, using the Ephemeris of the

German astronomer Regiomontanus.

When Ovando finally allowed Mendez into Santo Domingo, there were no ships

available for organizing the rescue of Columbus's stranded expedition.

In the end, Mendez was able to charter a small caravel, which arrived at

Jamaica on June 29, 1504, and rescued the expedition.

Columbus returned home to Spain on November 7, 1504, completing his final expedition

to the West Indies.

|

| 1506 |

|

Although at first full of hope and ambition, an ambition partly gratified by his title

"Admiral of the Ocean Sea," awarded to him in April 1492, and by the grants enrolled in

the Book of Privileges (a record of his titles and claims), Columbus died a disappointed man

on May 20, 1506.

Columbus' remains were first interred at Valladolid.

In 1542, however, the bones of Columbus were taken from Spain to the Cathedral of Santo

Domingo in Hispaniola (now the Dominican Republic).

|

According to the older understanding, the discovery of the Americas was a great triumph,

one in which Columbus played the part of hero in accomplishing the four voyages, in being

the means of bringing great material profit to Spain and to other European countries,

and in opening up the Americas to European settlement.

The more recent perspective, however, has concentrated on the destructive side of the European

intrusions, emphasizing, for example, the disastrous impact of the slave trade and the

ravages of imported disease on the native peoples of the Caribbean and the American continents.

The sense of triumph has diminished accordingly, and the view of Columbus as a hero has now been

replaced, for many, by one of a man deeply flawed, ruthless and responsible for the misfortune

of the native people on the American continent.

While Columbus' abilities as a navigator and his sincerity as a man are rarely doubted,

in today's perception, he is removed from his position of honour.

|